The remarkable journey of luxury wallpaper

When walls become narrative, material and architecture

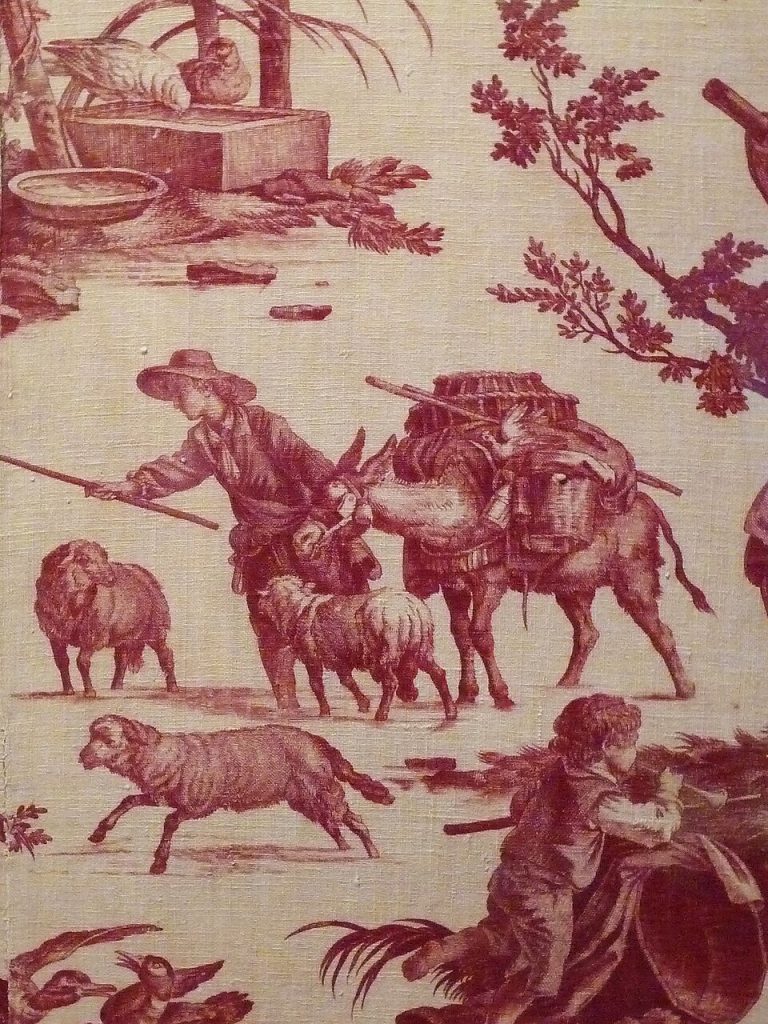

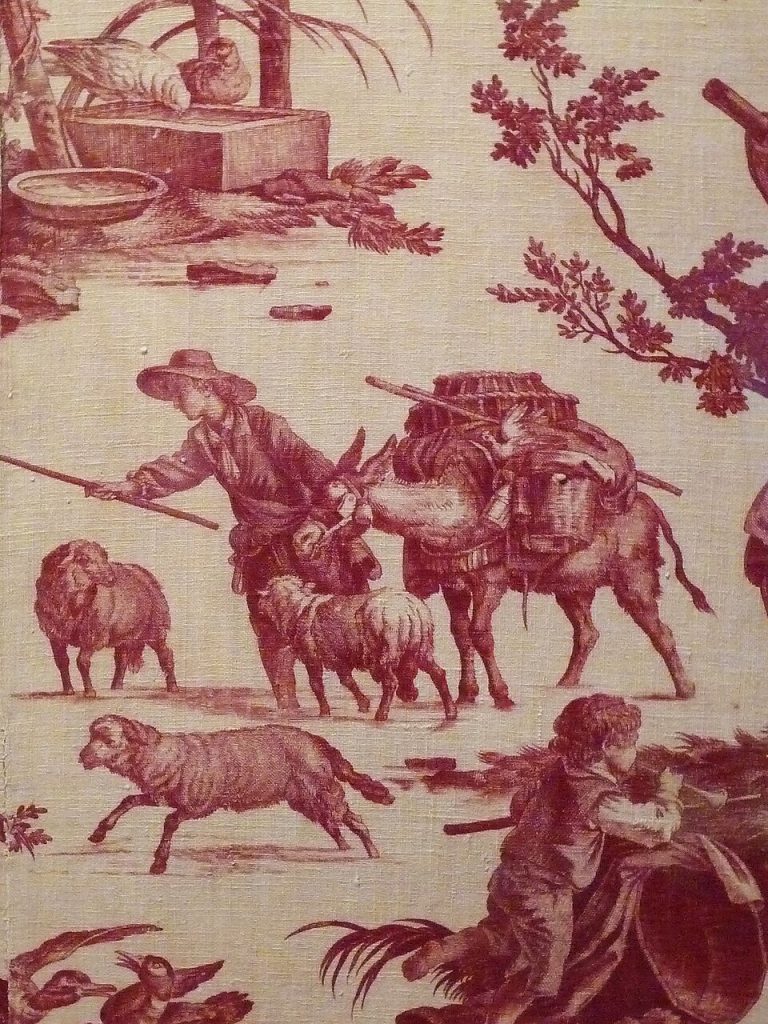

Les occupations de la ferme, Jouy-en-Josas, manufacture Oberkampf, dessinateur Jean-Baptiste Huet, vers 1785-1792, toile de coton imprimée à la plaque de cuivre. Ji-Elle – Wikimedia

Long confined to the role of a decorative backdrop, wallpaper is now enjoying renewed recognition. In today’s most exacting interior projects, it no longer merely covers a wall: it structures space, engages with architecture and anchors interiors within a long lineage of gestures, techniques and visual cultures.

The story of luxury wallpaper is that of a mural art in its own right -one that predates industrialisation and has been shaped by cultural exchange, technical innovation and shifting tastes over centuries.

Les occupations de la ferme, Jouy-en-Josas, manufacture Oberkampf, dessinateur Jean-Baptiste Huet, vers 1785-1792, toile de coton imprimée à la plaque de cuivre. Ji-Elle – Wikimedia

Lin Amd – Pexels

Origins: an imperial wall art

Lin Amd – Pexels

The history of wallpaper begins in China before the year 1000. From the 8th century onward, large sheets of paper or fabric were hand-painted to adorn the walls of palaces and aristocratic residences. Unlike later European production, these early wall coverings were not conceived as repeating patterns but as expansive pictorial scenes, designed to envelop the space.

Their chromatic precision and attention to detail established an enduring standard for luxury wall decoration. Ironically, these Chinese wallpapers — produced largely for export — were rarely used domestically. Imported into Europe from the 16th century through trade in silks, lacquers and porcelain, they quickly became prized by Western elites. Their technical sophistication and narrative power profoundly influenced European makers, who sought to decipher their secrets.

Europe discovers wallpaper

Pxhere (détails)

By the 16th century, Europe had begun developing its own solutions. In France, dominos appeared as early as 1514: paper sheets printed with wooden blocks for outlines, then coloured by hand. These versatile objects were used not only on walls, but also on furniture, boxes and book bindings -hybrid artefacts at the crossroads of graphic craft and interior decoration.

A decisive shift occurred in early 18th-century England, when manufacturers began gluing sheets together into continuous rolls before printing. This innovation gave birth to wallpaper as we know it today: a continuous surface designed to cover entire walls. Block printing soon enabled increasingly complex polychrome motifs, often inspired by contemporary textile patterns.

Pxhere (détails)

Brian Ramirez – Pexels

The textile illusion: the golden age of flocked wallpaper

Brian Ramirez – Pexels

One of the era’s most significant innovations was flocked wallpaper. In 1634, in London, Jerome Lanier developed a method of applying coloured wool powder onto varnished motifs, creating a remarkably convincing imitation of velvet and silk damasks.

These wallpapers were an immediate success. Less costly than textiles yet durable — and conveniently moth-resistant thanks to the turpentine used in the adhesive — they became widespread. By the 18th century, few English homes lacked at least one room decorated with flocked wallpaper. The wall became tactile, almost textile in nature, and wallpaper emerged as a credible alternative to tapestries.

The 18th century: wallpaper as a statement

DUFOUR (manufacture) ; CHARVET Jean-Gabriel (dessinateur) – Les sauvages de la mer du Pacifique ; les voyages du capitaine COOK (titre d’usage) ; Paysages indiens (titre d’usage) – Wikimedia

In France, excellence found its embodiment in the factory of Jean-Baptiste Réveillon, founded around 1750. As the first royal wallpaper manufactory, it elevated the medium to new heights through refined backgrounds, masterful colour palettes and complex printing techniques. Wallpaper was no longer a substitute; it became a deliberate aesthetic choice.

This ambition culminated in the rise of panoramic wallpapers. At the beginning of the 19th century, Joseph Dufour produced Les Sauvages de la mer du Pacifique (1804), a monumental composition printed across vast strips. These immersive decors transformed salons and staircases into narrative landscapes. Wallpaper ceased to be a pattern — it became a story.

DUFOUR (manufacture) ; CHARVET Jean-Gabriel (dessinateur) – Les sauvages de la mer du Pacifique ; les voyages du capitaine COOK (titre d’usage) ; Paysages indiens (titre d’usage) – Wikimedia

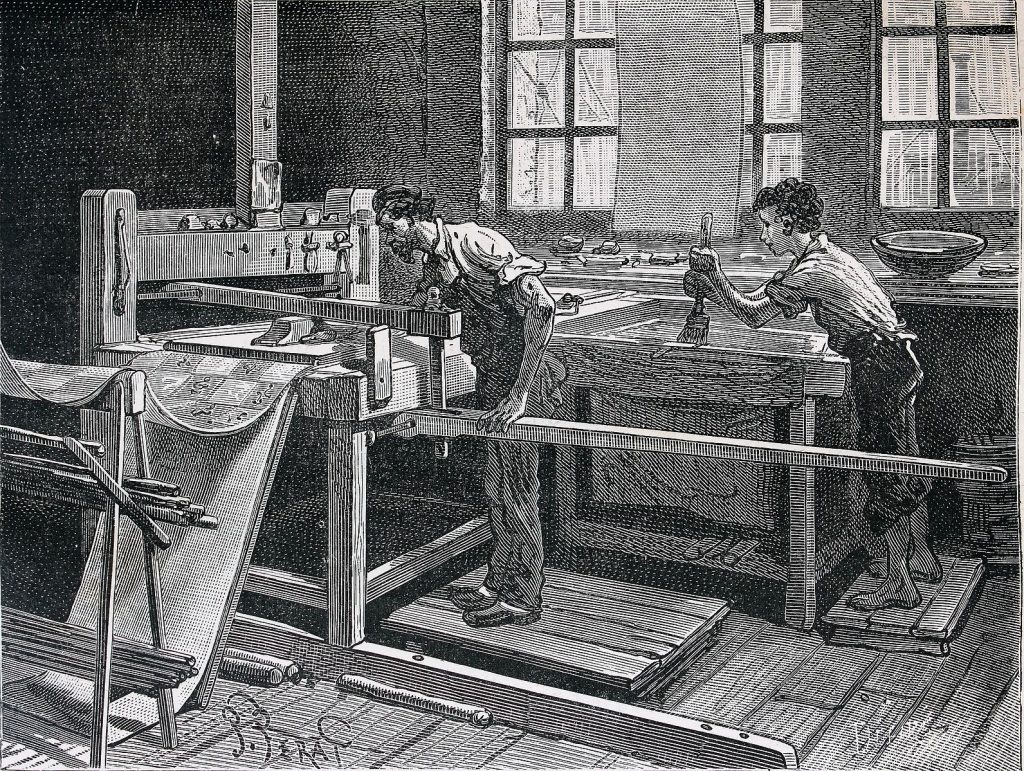

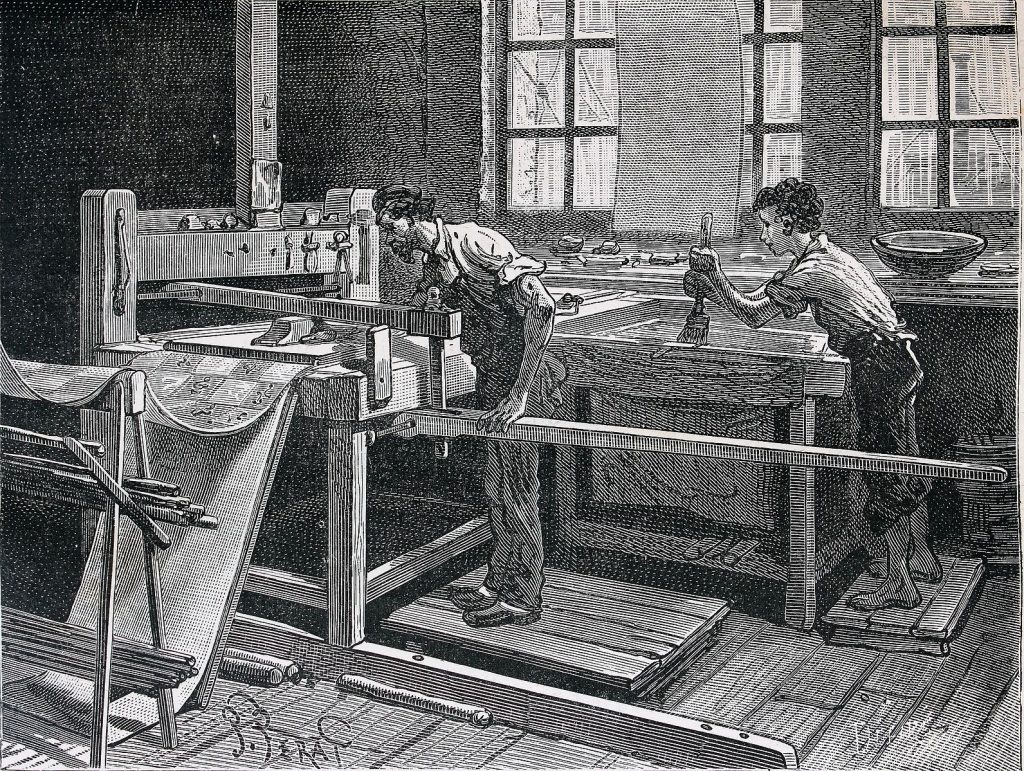

Les merveilles de l’industrie ou, Description des principales industries modernes / par Louis Figuier. – Paris : Furne, Jouvet, [1873-1877]. – Tome II – Fondo Antiguo de la Biblioteca de la Universidad de Sevilla – Wikipedia

Industrialisation and controlled democratisation

Les merveilles de l’industrie ou, Description des principales industries modernes / par Louis Figuier. – Paris : Furne, Jouvet, [1873-1877]. – Tome II – Fondo Antiguo de la Biblioteca de la Universidad de Sevilla – Wikipedia

The 19th century brought major technical breakthroughs. The invention of continuous paper around 1830 enabled mechanised production. Printing machines — first manual, then steam-powered — multiplied rapidly. In 1839, Potters & Ross patented the first roller-printing machine; by 1841, C.H. & E. Potter had refined the process. British production soared from one million rolls in 1834 to nearly nine million by 1860, while prices fell sharply.

Yet industrialisation did not erase luxury. On the contrary, manufacturers competed through innovation: embossing, gilding, satin finishes and trompe-l’œil effects. Wallpaper imitated marble, Cordovan leather, Lyon silks and winter-garden foliage. It became a tool of architectural illusion, capable of reshaping spatial perception.

Wall, surface and illusion: aesthetic debates

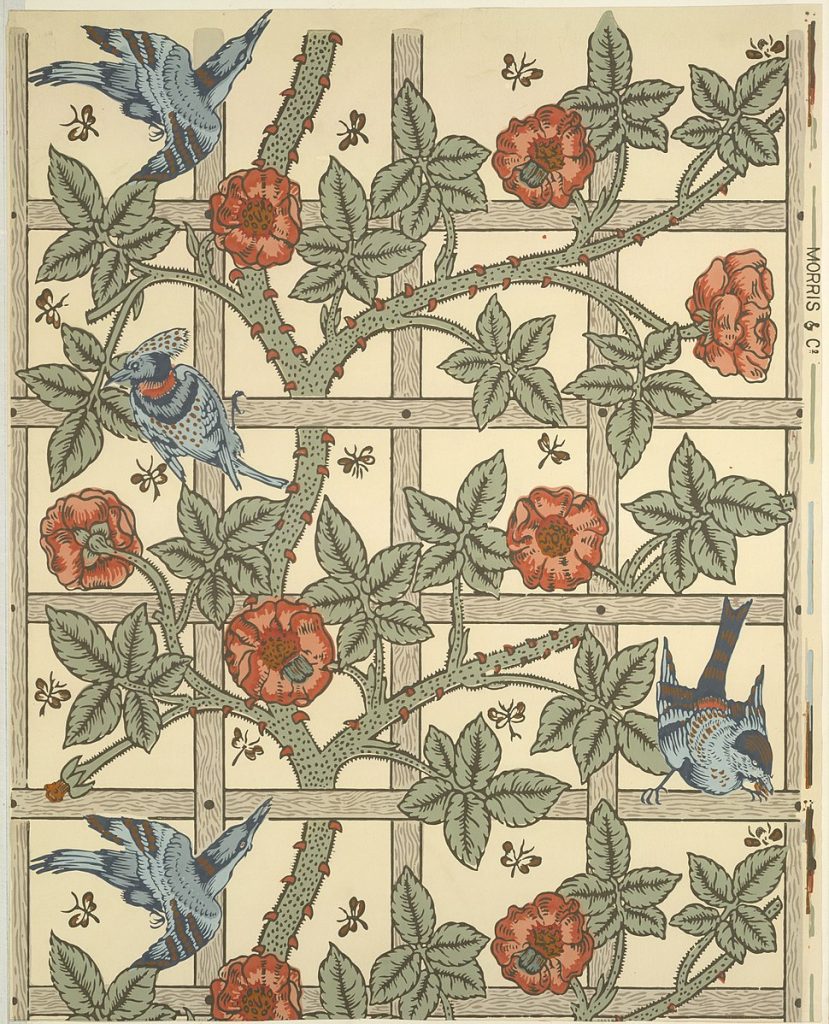

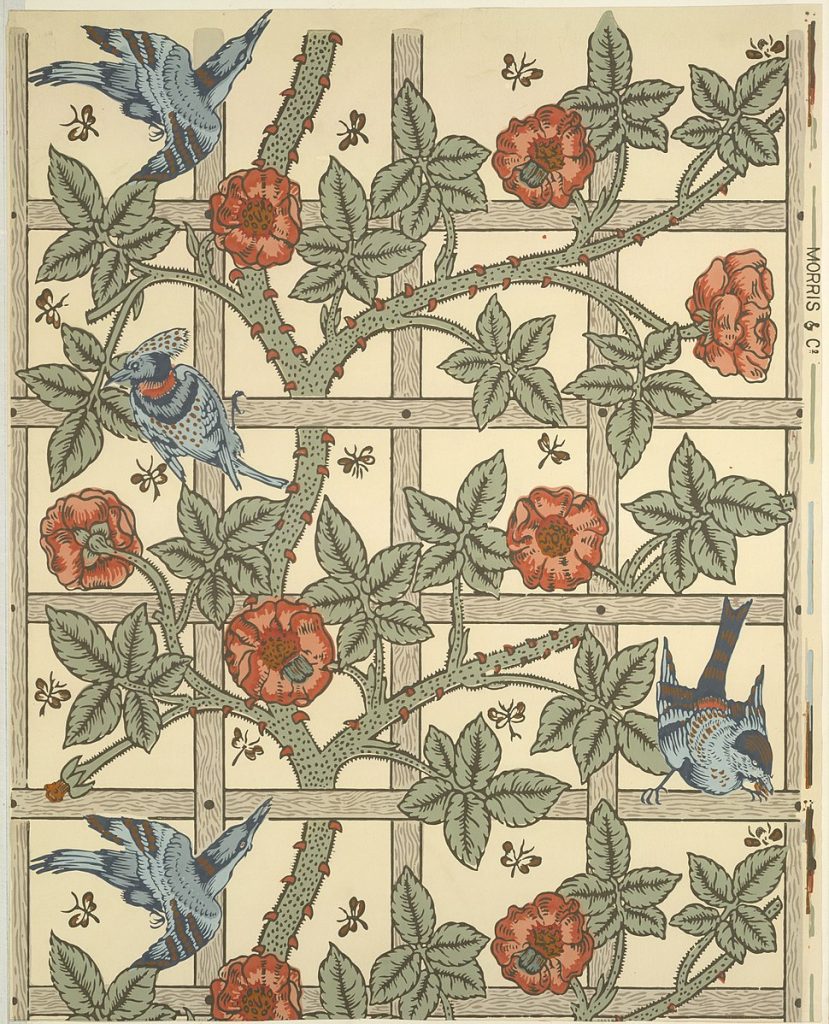

Trellis, papier peint, William Morris, Birds designed by Philip Webb, Morris & Company (MET, 23.163.4h) – Wikimedia

This decorative abundance also sparked debate. In the mid-19th century, figures such as architect A.W.N. Pugin criticised the excessive naturalism of Victorian motifs, arguing that they contradicted the inherent flatness of the wall. Owen Jones advocated a return to abstraction, symmetry and disciplined ornament.

It was William Morris who forged the most enduring synthesis. Designing over fifty patterns, Morris observed nature directly, distilling it into stylised organic forms that were neither illusionistic nor purely geometric. Trellis (1864) and Willow Bough (1885) exemplify this approach. Wallpaper became the bearer of an ideal: accessible art rooted in everyday life.

Trellis, papier peint, William Morris, Birds designed by Philip Webb, Morris & Company (MET, 23.163.4h) – Wikimedia

Walter Crane, The Sleeping Beauty, le château endormi – Picryl

From domestic decor to specialised uses

Walter Crane, The Sleeping Beauty, le château endormi – Picryl

By the late 19th century, wallpaper adapted to increasingly specialised interiors. The frieze–filler–dado system structured walls into functional layers, balancing durability and visual rhythm. Wallpapers designed specifically for children’s rooms emerged. In 1879, Walter Crane created Sleeping Beauty, a washable, arsenic-free wallpaper intended to support children’s well-being and imagination.

The 20th century: modernity, decline and revival

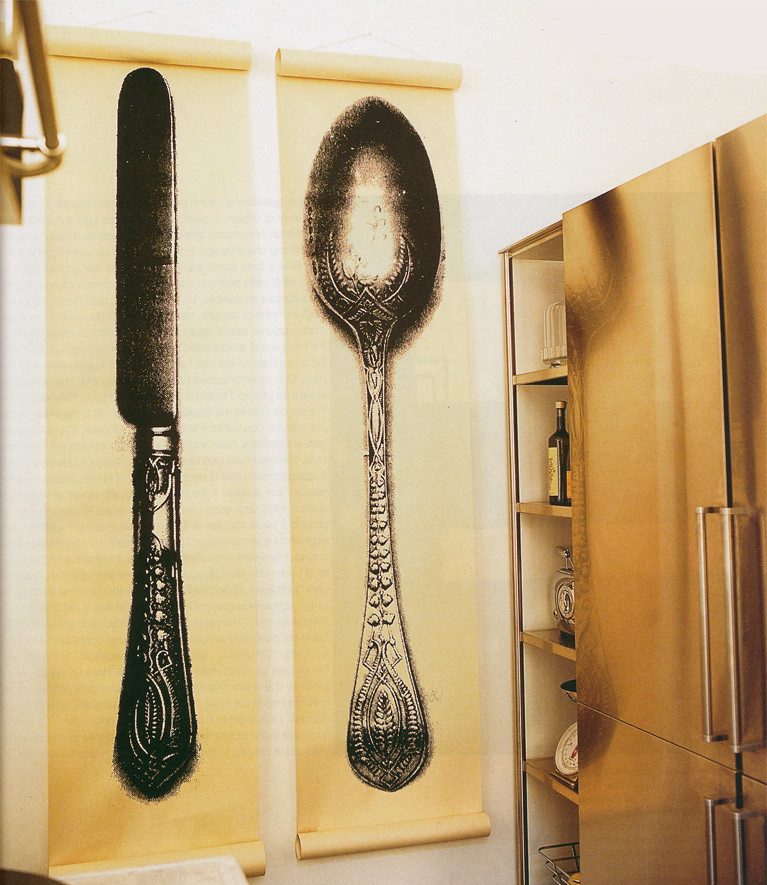

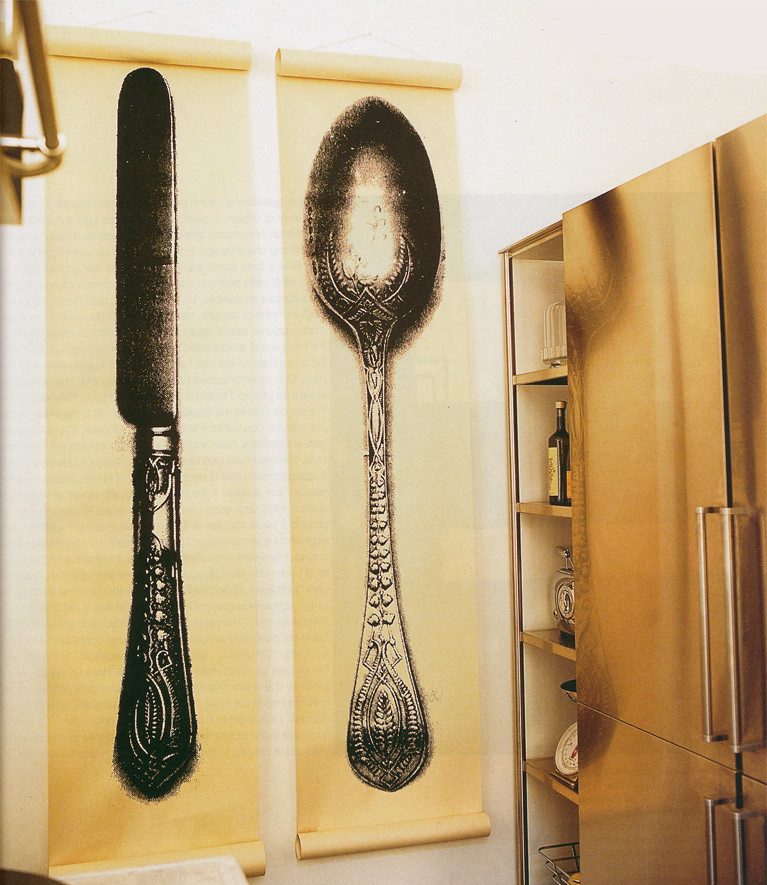

Flickr – Tracy Kendall Wallpaper

Throughout the 20th century, wallpaper mirrored artistic movements of its time. Jazz-age graphics, Cubism, Orientalism and Egyptomania flourished in the 1920s and 1930s. Production peaked at nearly 100 million rolls in 1939. Post-war modernism favoured abstraction, followed by the bold colours of Pop and Op Art in the 1960s.

Technical innovations multiplied: pre-pasted wallpapers (1961), metallic finishes, washable vinyls. The oil crisis of 1973 weakened the industry, and paint emerged as a competitor. Wallpaper briefly lost its prestige.

From the 2000s onward, however, a renaissance took place. High-definition digital printing, contemporary screen printing and limited editions reconnected wallpaper with artistic expression. Designers such as Deborah Bowness, Tracy Kendall and Timorous Beasties approached the wall as installation rather than surface.

Flickr – Tracy Kendall Wallpaper

Photo de Mehmet Turgut Kirkgoz – Pexels

Luxury wallpaper today: an architectural material

Photo de Mehmet Turgut Kirkgoz – Pexels

Today, luxury wallpaper is fully recognised as an architectural material. Premium non-woven substrates, complex textures, material effects and the integration of resin beads or metallic primers combine technical performance with visual richness. Durable, washable and stable, wallpaper conceals imperfections while enabling bold yet reversible interventions.

For architects, it has become a powerful storytelling tool — capable of giving spaces immediate identity and interacting with light, volume and use.

Manufacturers and publishers: a living heritage

French houses such as Élitis, Isidore Leroy, Casamance, Papiers de Paris, Ananbô and Le Grand Siècle uphold this tradition, blending innovation with craftsmanship. Internationally, Cole & Son, Osborne & Little, Designers Guild and Little Greene embody a British lineage where wallpaper remains inseparable from domestic culture.

Luxury wallpaper is neither relic nor ornament. It is a living memory, a sensitive surface that continues to evolve without losing its emotional resonance. For contemporary designers, it offers a rare field of expression — where history, technique and vision converge.

French luxury wallpaper manufacturers

French publisher of high-end wallpapers, textures and panoramas, offering varied collections (plain, textured, patterned and hand-painted motifs) designed for residential or contract environments. Its wall coverings frequently incorporate materials and effects sought after in demanding projects.

- Official website :

- https://elitis.fr/en/collections/walls

Historic French company specialising in traditional and panoramic wallpapers, renowned for its refined patterns and artisanal heritage.

- Official website :

- https://isidoreleroy.com/en

French brand offering wallpapers, wall coverings and decorative textiles with a timeless and sophisticated aesthetic, combining meticulous detail with stylistic diversity.

- Official website :

- https://www.casamance.com/en/

French specialist in reproductions of exceptional historical and panoramic decorations, often produced under museum licences and featuring large-scale heritage-inspired compositions.

- Official website :

- https://www.papiersdeparis.com/

French publisher reviving 18th- and 19th-century decorative schemes from museum collections. Its panoramic wallpapers and motifs reinterpret a rich decorative heritage for contemporary interiors.

- Official website :

- https://www.legrandsiecle.com/en/

High-end studio specialising in murals and panoramic wallpapers, created from original designs or inspired by historical landscapes and motifs. Particularly suited to exceptional projects, hotels and prestigious residences.

- Official website :

- https://www.ananbo.com/en/

International companies

Iconic English luxury wallpaper house founded in 1875, renowned for its heritage patterns, graphic identity and artistic collaborations.

- Official website :

- https://cole-and-son.com/

British manufacturer celebrated for bold wallpapers and innovative textures, blending contemporary trends with reinterpreted classic designs.

- Official website :

- https://www.osborneandlittle.com/

British manufacturer of premium wallpapers and paints, drawing on historical archives to reinterpret patterns for both classic and contemporary interiors.

- Official website :

- https://www.littlegreene.fr/papier-peint

Luxury wallpaper is neither a relic nor a mere decorative accessory. It is a living memory — a sensitive material that has withstood time without losing its emotional power. For contemporary architects, it offers a unique surface of expression: a place where history, technique and vision converge.

Continue in this issue :

Do you like WeAreKollectors® ? Talk about it on social media !

Site by FORGITWEB